Growing economic inequality and a lack of affordable housing options in Washington’s Methow Valley are forcing some residents and local businesses to take drastic steps to find homes and keep employees.

Housing is a basic need. A home can provide stability. It’s where kids are raised and meals are shared. Home is where we recharge and prepare for the next challenge. What would you do if you had a job but couldn’t afford a house or find a rental in your town? How do you think you would handle having to sleep on someone else’s couch?

I bought my first house in 2013. It was a 1,600 square foot starter home east of Portland, Oregon. It cost $211,000. This was in the good old days when the sale price was pretty close to the list price and I had more than a few hours to make an offer. I even had time to do a few test commutes and explore the neighborhood.

At that time there were incentive programs available for first-time buyers, and I needed all of the help I could find. I didn’t have 20% to put down. I scraped together five or six thousand dollars, and most of that came from family. The monthly mortgage payment worked out to $1,400 a month. I lived in that house for five years and didn’t do much to improve it. If anything, it was probably in worse shape when I sold it, thanks to pets and kids. I sold it in 2018 for just over $320,000. It was only on the market for three days.

Today in the Pacific Northwest, full cash offers for thousands of dollars over the list price aren’t unheard of. The market has become so competitive that some buyers are making offers without ever seeing a property in person.

Finding affordable housing in more populated urban areas is challenging. That challenge is amplified in some rural communities where inventories are low and demand is growing.

Washington’s Methow Valley is a spectacular 70-something mile-long stretch of arid desert, alpine forests, and glorious mountains. The Valley’s communities are sandwiched between the Columbia River to the east and North Cascades National Park to the west. Summers bring hikers, backpackers, bikers, and climbers. Parking lots are full of adventure vans. Winters are a white wonderland for cross country skiers.

The main mountain pass from the west side of the state closes in the late fall due to snowfall, further isolating these close-knit communities.

I’ve met several locals who told me variations of the same story – they came to the Methow for the outdoors first and figured out the other parts of their life second. But a lack of affordable housing is making it challenging for some to keep the Methow as their home.

TwispWorks is a nonprofit that focuses on economic and community development in the Methow Valley. They recently released the largest and most comprehensive economic impact study the Valley has ever seen. Over 18 months, TwispWorks and its partners, combined data from public agencies and surveyed hundreds of residents and businesses to determine the state of economies and their evolving communities.

According to the study, the Methow Valley’s estimated population is just under 11,000. That accounts for 6,400 full-time residents and 4,380 part-time residents. Twisp and Winthrop are the largest communities reporting 2,605 and 2,431 full-time residents, respectively.

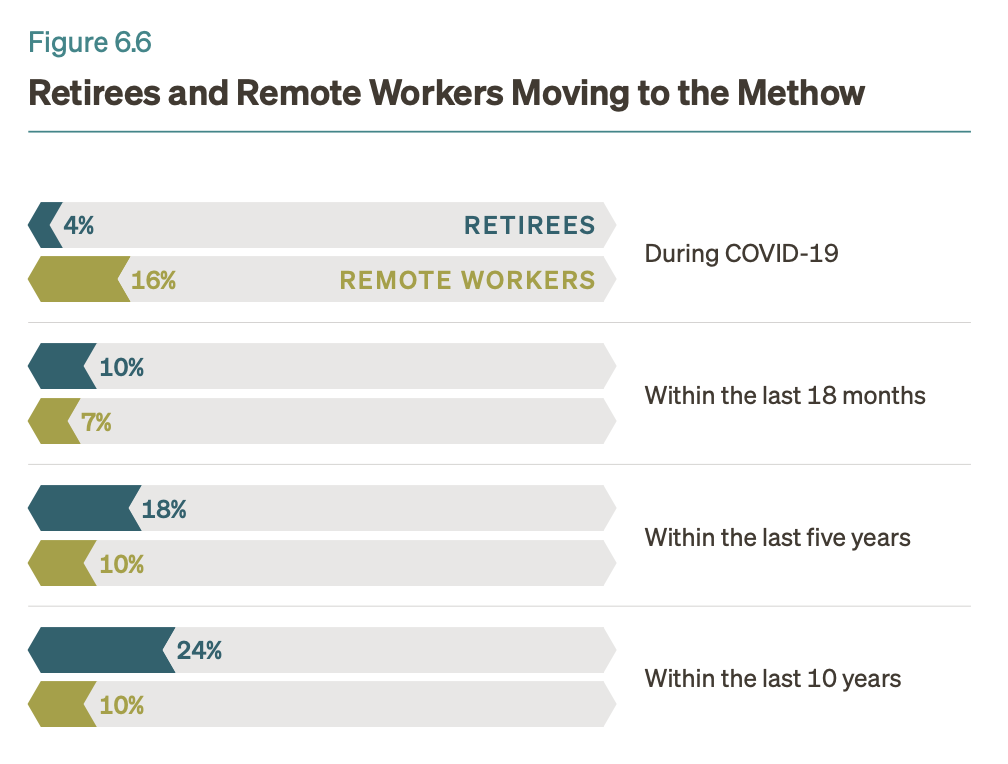

Prior to Covid-19, the populations in Winthrop, Twisp, and Mazama were growing. But when remote work became the foreseeable future, many employees moved to, or bought second homes in more rural communities, like the Methow Valley.

Infographics from the TwispWorks Economic Impact study of the Methow Valley

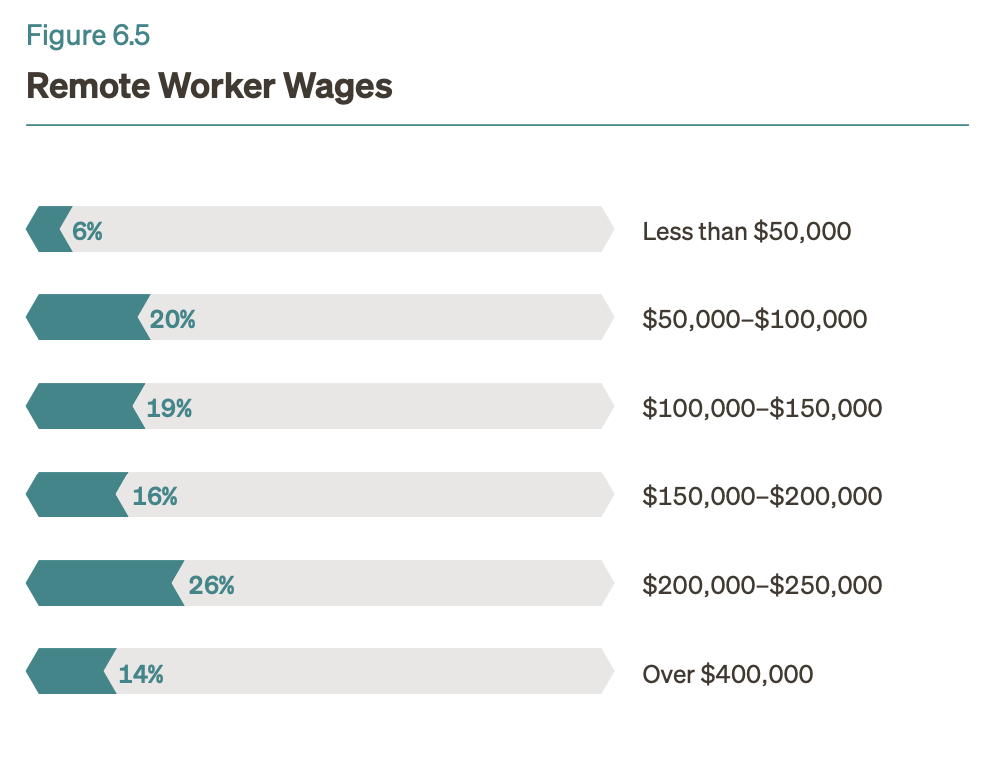

US Census data in the study shows that the 2020 median household income for local residents in the Methow Valley was $57,750. That accounts for people who live and work in the Valley. Out of 133 responses from remote workers who were surveyed – people who live in the Valley but collect a paycheck from companies outside of the area – the median wage of an individual remote worker was $202,000 per year. Given that the remote employees self-reported, there could be some fluctuation in those income numbers. But even if they’re in the neighborhood of accurate, the numbers show that remote workers brought in close to five times more than the average local household income.

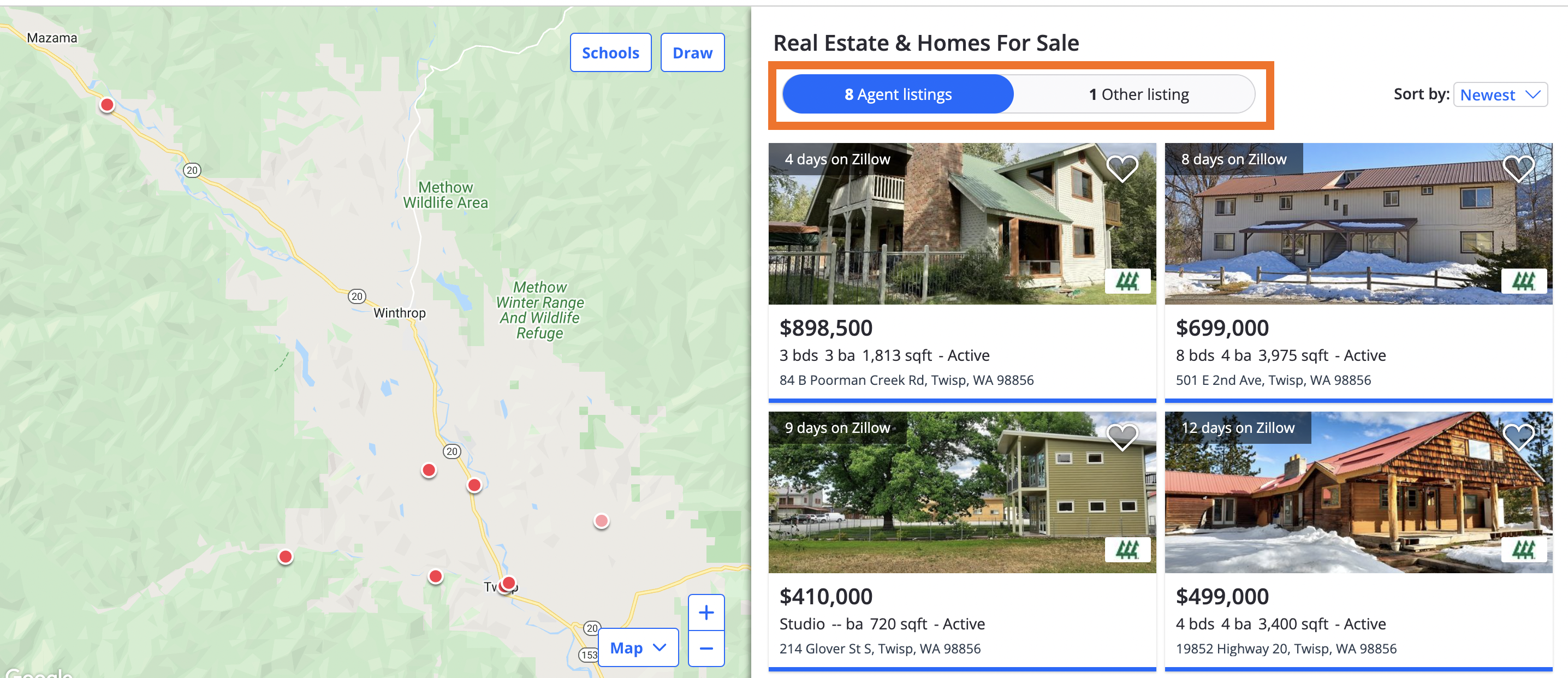

In 2016 the average cost of a home in the Valley was $272,000. By June 2020 the average price climbed to $473,000. There’s also the issue of supply and demand. The TwispWorks study points out that there were only 13 homes on the market in January 2021. Five of them were listed at $900,000 or more and two of them were not eligible for traditional financing.

There are several factors that go into calculating a realistic mortgage payment. Things like the size of down payment, interest rates, and private mortgage insurance (PMI). But the generic 28% rule says that a mortgage payment should not exceed 28% of your monthly gross income. The median income for a household of two Methow Valley residents is $51,500. That’s around $4,300 gross. Using some basic estimates for taxes in Washington state, that works out to roughly $3,700 take home per month.

The monthly mortgage payment for a $473,000 (the June 2020 average price in the Methow) home works out to roughly $2,700. That figure accounts for 20% down but will vary with interest rates, taxes, and insurance. 28% of the gross monthly income for a two-person household in the Valley is about $1,200. If you consider the net monthly income – $3,700 – that number is closer to $1,000 per month.

2021 real-estate data from Windermere-Methow paints an even more dire picture of the Methow Valley’s affordable housing crisis. The number of available single-family homes continued to trend down with an overall 33% decrease in inventory. The average sale price increased to $646,848 – up 40%. The median sale price climbed 25% to $525,000. Inventory is down. Demand is up.

All of those incomes and estimated mortgage payments make it clear that buying a home in the Methow Valley is out of reach for many locals. Using that 28% rule, the local household of two would need to come up with an additional $1,500 each month just to cover the mortgage for the average home in the area.

The Valley relies heavily on tourism which is supported by seasonal and hourly workers. I’ve spoken to several business owners who have all experienced staff shortages at least partially due to limited housing options. One local worker told me that finding a rental was like hitting the lottery.

The options are limited for people who can’t find a stable living situation. Some have to expand their search outside of the Valley, which can mean long commutes, more costs in gas, and dangerous driving conditions over passes. Some people couch surf while they look for a more permanent situation. And there are the people who choose to leave the Valley entirely.

Methow Valley-based Old Schoolhouse Brewery (OSB) makes delicious beer. If you like hazy IPAs, try their Eddy Hopper. It was OSB’s first hazy and the only one I need in my fridge. Their pub in Winthrop has some of the best riverfront eating you’ll find. The taproom in Twisp on the TwispWorks campus is a great jumping-off point for exploring nearby downtown. And the soon-to-be Mazama Public House will be managed by OSB.

Jacob Young is one of OSB’s partial owners and the general manager. He and his business partners bought the brewery in 2016 and have grown to become one of the larger employers in the area. Affordable housing has a direct impact on local businesses as they struggle to find and keep workers. The situation has become so desperate that Jacob has opened up his own home to employees who need a place to live.

“I installed a little kitchenette in the downstairs of our house. We now have a little mother-in-law. One of our brewers - a female brewer - was getting evicted because the landlord was converting their long-term rental into a nightly-rental, so he could bring in more money. She was going to have to leave the valley. And I just absolutely refused to lose her. She’s a wonderful asset to our business. To have a female brewer is a really cool thing. It’s definitely a male-dominated industry, unfortunately. She brings an amazing perspective and she’s awesome. She and her partner live downstairs and that’s working out really well.”

Jacob Young, General Manager & Partial Owner of Old Schoolhouse Brewery

If people can’t find a stable place to live, their ability to work suffers. Jacob told me about two long-time employees who had to move to a neighboring community when they couldn’t find housing close to OSB. They ended up with an hour-long commute each way which cost them over $400 a week in gas. The employees had to take on even more work just to make up for the added cost of the commute.

The Methow becomes a winter wonderland during the colder months of the year and that means all of the treacherous driving conditions that come with snow and ice. How long would you navigate a long and expensive commute in potentially dangerous winter driving conditions to keep a job? Unfortunately, that’s a question some local Methow workers are having to answer.

Jacob is genuinely concerned about his staff’s safety and well-being. But the struggle for affordable housing also meant shifting OSB’s other investments.

In 2021, Jacob was searching for someone to help with the brewery’s sales. Up to that point, he was wearing multiple hats as GM, including selling the beer. He found the right person for the job, but that person couldn’t find a place to live in the Valley. They slept on couches for a while but needed a more permanent home. In July of that year, OSB made a new investment – a house in Winthrop.

“Out of necessity, we bought a home in Winthrop that we can use for staff housing. We saw an opportunity to buy a home that we could use for him and other employees who might need a better housing situation. It’s working out well. It’s a subsidized situation. It doesn’t cover all of our costs but it’s worthwhile for the business to spend money to maintain housing for these employees that we don’t want to lose. That’s the investment.”

Jacob Young, General Manager & Partial Owner of Old Schoolhouse Brewery

In the summer of 2021 wildfires scorched over 100,000 acres in the Methow Valley . The Cedar Creek and Club Creek fires burned homes and forced residents to evacuate. Before the fires started, Covid restrictions were easing up and there were glimmers of normal life ahead. Strained local businesses were still dealing with the impacts of housing and staffing at that time, but they were also ready to welcome tourists back to the Valley and recover some of their losses. Then the fires hit and effectively shut down tourism.

“It was so hard. I sent my wife and kids off to the coast. It was so unhealthy. I’m not prone to depression. But it could have easily pushed some people over the edge. For our business, July and August are the two months out of the year that help us stay open seven days a week, year-round. That was taken away. It was abysmal. For the health of our employees, we closed when the air quality was really bad.”

Jacob Young, General Manager & Partial Owner of Old Schoolhouse Brewery

Although the fires cut into the important summer tourism months, business has stabilized, at least for OSB. In fact, early fall 2021 was so busy that Jacob scrambled to staff up to cover what is typically a slower time of year. With winter travelers and the Mazama Public House opening in 2022, Jacob is optimistic about OSB’s future.

The Methow Housing Trust (MHT) is one of the more prominent voices in the affordable housing discussion. The Trust builds homes on the land it owns in the Valley. Owning the land means they’re able to control the cost of homes for buyers and terms of the resale. At the time this story was published, the MHT has 21 occupied homes on two properties, with five more due to be completed soon. 38 additional homes are in the early planning stages. They currently have 45 families on their waitlist.

I spoke with Danica Ready, Executive Director of the Methow Housing Trust. I asked her how the Methow Valley can stave off the type of growth and development that other mountain and rural areas have seen. She told me that the Valley residents have a vision for their communities and they’re all working hard to realize that vision. I think she’s right. That vision is part of what attracts people to the Valley and its communities. The miles of trails that so many locals and tourists enjoy weren’t formed by big resorts. The Valley has an inspiring number of non-profits that work to protect the environment and support residents. You won’t find coffee shop chains or big box stores. None of these things are accidents. It’s that vision at work.

Several years ago I asked a resident who now works in real estate that same question – how can anyone really stop bigger development from taking hold in the area? He reminded me that ski resorts have tried and failed to establish a presence in the Methow. The Valley communities helped stop a copper mining operation near Mazama. He explained that many real estate agents will try to help educate new residents about the importance of participating in Valley communities.

The income disparity outlined in the TwispWorks study could lead you to the conclusion that remote workers, recent transplants, and second homeowners are the problem in the Methow. But those same people are also part of at least one solution. Most of the Methow Housing Trust is privately funded – that includes a lot of funding from those remote workers and second homeowners. The people who support the MHT recognize the lack of affordable housing in the Methow Valley and are using their dollars to help solve it.

In 2020 Wild Human published a story about CB Thomas. CB and his wife, Micki, previously ran Goat’s Beard Mountain Supplies in Mazama. CB also recognized the complicated relationship between locals and second homeowners. But he also acknowledged that those same transplant and part-time residents are investing in the Methow’s communities.

I make regular visits to the Methow Valley and have gotten to know some of the people that live there. I’ve tried to be transparent with those people about this story. And the truth is that there are some people who would prefer that I didn’t publish it. I understand where they’re coming from, at least as much as I can understand as someone who does not live in the Methow Valley.

When I first started exploring this story, I traveled to the Methow and visited with some of the people I’ve met along the way. I needed input. I also met with new friends. I remember the first time I met Dan and Meg Donohue from Blue Star Coffee Roasters. Blue Star had just broken ground on their new location in Twisp. Dan and Meg graciously carved out some time for me, a total stranger at that time, and let me ask them a bunch of probing questions. I remember Meg doing a bit of not-so-subtle probing of her own. She asked, “Why do you want to do this story? What are you after?” To be clear, Meg was incredibly kind during that first meeting. She and Dan have been nothing but kind to me. During my most recent trip, they gave me a tour of their beautiful new building. I can’t wait to get back there. But during that first meeting, Meg wanted to know why I want to write about the Methow Valley.

I remember sharing a beer at a picnic table with CB Thomas late one winter evening. We talked about my idea to do more stories about the Methow Valley. I asked him for his honest opinion. He told me that he was generally supportive as long as I write about the real Methow Valley. CB said that a lot of people publish romantic stories about the Methow, but that a lot of them fail to highlight the problems that he, and other residents, are facing. Stories focus on the natural beauty, and the quaint towns. But there’s also poverty, income disparity, issues with water usage, and of course, a lack of affordable housing. He said, “Just don’t make this place seem like Shangri-La. It isn’t.”

Housing is a complicated issue. There isn’t one solution or explanation. Recently the Seattle Times published a long story about affordable housing in the Methow Valley. The reporter included some important community voices in the article and helped explain some of the factors that are contributing to the housing issue.

I’ve met with several people in the Valley who have been more than willing to talk to me, but asked that I leave their names out of this story. The Methow Valley is stressed. Any attention, even positive, can sometimes be perceived as negative. I’ve tried to write this story with all of that in mind. But I’ve also consistently been asked why I want to write this story.

I, and so many others, have a connection to the Methow Valley that’s difficult to explain. One of the things that I find so interesting is the sense of community and what it means to people who live there. Over time I have come to understand that my fascination isn’t just about the Valley’s landscapes or the people. It’s how those two things relate and interact with each other. The more I learn about affordable housing in the Valley – and some of the solutions that have been offered or are already in place – the more I learn about the people who live there.

Soaring real estate prices and a lack of affordable housing are not unique to the Methow Valley. I’ve listened, read, and watched coverage about affordable housing from around the country. I’ve heard people blame capitalism or unnecessary government regulations. I’ve read online comments that echo those same political and ideological talking points. But in this case, I’ve been able to listen to stories about the human impact of the housing issue in the Methow Valley. People like Jacob from OSB, CB Thomas, Dan and Meg from Blue Star, and all of the people who have asked me to leave their names out of this story have all shared with me the impact on their lives and businesses, and the lives of their neighbors. Those people are why I wanted to write this story.

What motivated me to pursue this story is not dramatically different than what inspired Wild Human. A powerful story can help align solutions. Old School House Brewery bought a house because some staff couldn’t find a place to live. They invested in their people in a way that most of us don’t have to think about. That’s powerful and inspiring.

Capitalism and regulations might be part of the ultimate solution to this complicated issue. But I don’t think that’s the most important part of the discussion. Taking care of our neighbors is important. Recognizing that basic human needs are not being met is important. Supporting those people, organizations, and communities that are trying to remedy that and build the type of vision that exists in the Methow Valley is important. I think that vision is worth protecting.

Learn more about how you can support the Methow Housing Trust and their ongoing efforts to offer affordable housing in the Methow Valley here.